Critiquing Action Fantasy #1: Necrosha

So I recently discussed how I want to critique superhero comics in a manner that specifically analyzed it as genuine action fantasy. This decision means that I embrace what superhero comics are, and I do not need for them to be high-class, high-art. This perspective is also why I have always thought many criticisms of the superhero genre are without merit. Would you criticize a Western for having dialogue like "Y'all?" Would you hold it against a Romance if a lover says, "You set my heart on fire?" Likewise, it seems silly to accuse superhero comics of having trite dialogue and then stating that this is the main problem with the genre. Putting the words of Shakespeare into a comic does not automatically improve the storytelling conventions of superheroes (though it does look kinda cool):

Superhero comics are about action, fighting, and epic storytelling told through a modern lens. It is my contention that current superhero comics have often lost their way, and in trying to be different from what they actually are, they frustrate both readers who just want good action and those seeking for greater depth. Improving superhero comics, therefore, involves boiling down the essence of the superhero action story and finding out how to improve aspects of its unique brand of storytelling.

Some Background Information

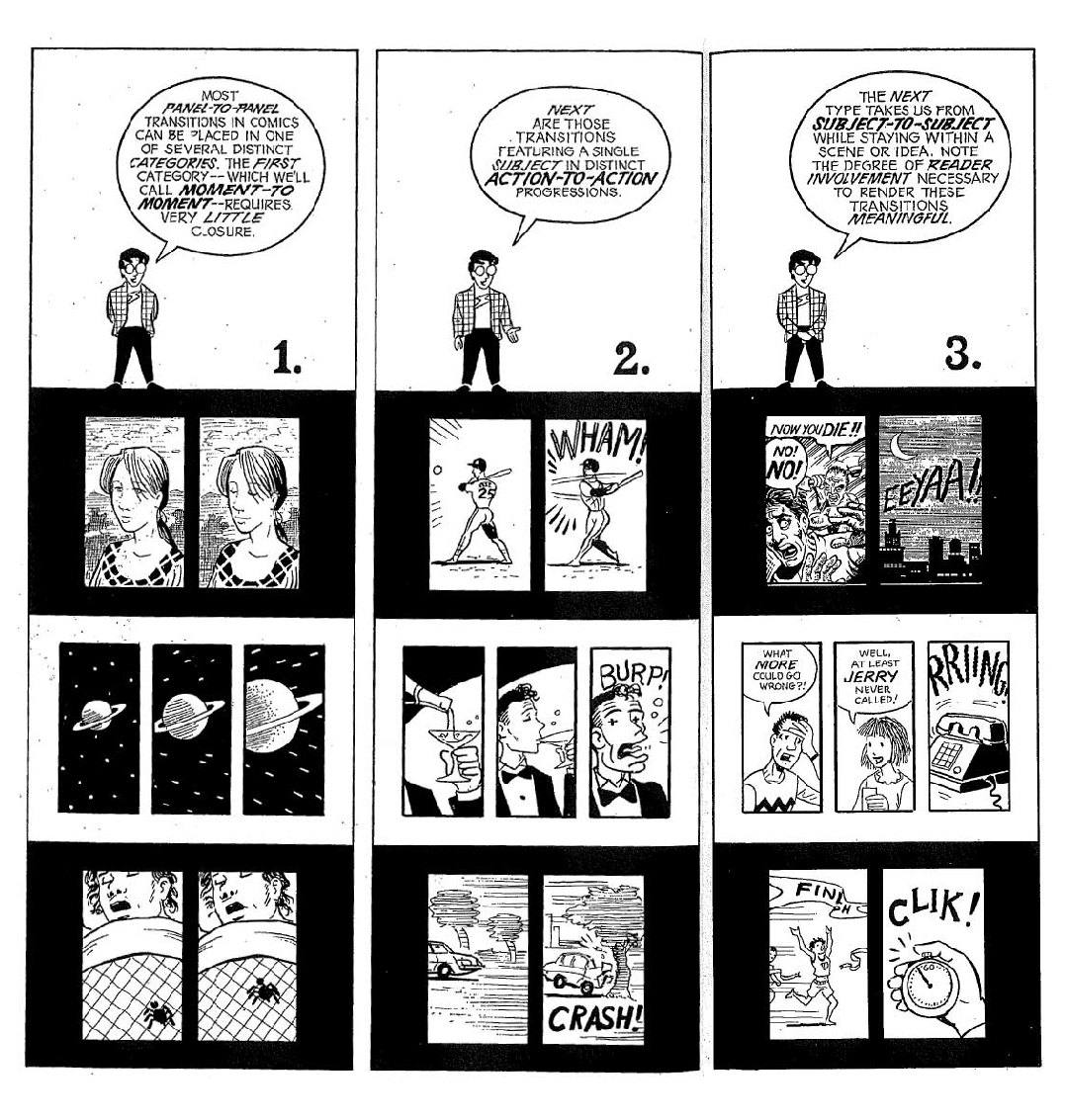

First, it is important to understand a little background terminology to lay the groundwork of our discussion. Scott McCloud, in his seminal piece Understanding Comics, breaks down panel transitions into several categories. Only the first three he mentions are particularly relevant to our discussion:

As comics are a graphical medium told through sequential images, each one of McCloud's panel transitions relates a specific period of time; therefore, the paneling used in a superhero comic relates a story to the reader in a particular way.

It is important to note, as McCloud does here, that each type of transition requires a different level of imaginative effort for the reader to create closure or meaning between the gaps in the panels. Unlike a film, where the audience sees every frame of action in many cases, the language of comics requires for a reader to fill in the blanks with what is supposed to have happened between the panels. Thus, moment-to-moment transitions require very little effort to piece together what happened in the gaps (or gutter, as it is often called) between panels, and it often therefore denotes only a minuscule amount of time has passed between them. Conversely, subject-to-subject transitions require much more effort to parse out what has occurred in the gaps, and they often denote a much longer period of time has passed.

Now, McCloud notes that by his count, a typical Marvel superhero story of the Kirby era had about 65% of its panels as the action-to-action type. The vast majority of these action oriented stories focused upon smaller periods of time, specifically upon small skirmishes and battles. A page from Spider-Man's first battle with Dr. Octopus exemplifies these principles:

Now, while this early superhero battle is fairly basic in its background detail and its framing of individual shots, it is a prime example of portraying action. In panel one, Spider-Man leaps out of the way of two of Dr. Octopus's tentacles as they strike forward. Two actions in this panel have occurred. In panel two, Spider-Man recoils in pain as another of Doc Ock's tentacles strikes him. Again two actions have occurred. The reader can quickly process these images, filling in the blanks and perhaps imagining exactly where on Spider-Man's body Doc Ock's blows have landed. In panels four and six, Dr. Octopus can be seen struggling to free himself from Spider-Man's webbing. Again, the reader can imagine exactly how Dr. Octopus is struggling, completing the action in panel six. On the whole, although rudimentary, this page feels full of the action that is in keeping with the superhero story.

The Decompression/Compression Phenomena

With this mortar of theory laid into place, we can begin shifting our attention to a piece that demonstrates how differently modern superhero stories pace themselves. Modern superhero stories have often been accused of something called the decompression effect. Stuart Moore details the concept of decompression in this way:

There’s a lot of debate these days about the pacing of modern comics. Many mainstream books today move their plots along more slowly than fans are used to. This can play out in different ways: extended, realistically-paced dialogue scenes; long, cinematic action sequences; slow buildups to establish a protagonist’s origins and motivations.

Proponents of this new pacing call it “decompression” and argue that it allows for greater depth of character and mood. Opponents denounce it as mere padding, and argue that the rise of the trade paperback format has led writers to stretch out stories beyond their natural length.In superhero comics, if a story is told very quickly, it is thought to be compressed whereas it is decompressed if it is told more slowly.

I would like to add an additional observation to this phenomena. It is my belief that modern comics often employ a tension between compression and decompression. This plays out in superhero comics as a decompression of emotional story moments and continuity references on the one hand, and a compression of the action story elements on the other. This exaggerated compression of action is where I find that modern superhero comics have failed to embrace the essence of the genre.The choices of paneling in modern superhero stories compress the action of these stories to such a degree that readers gain very little from them, while the in-comic referencing to other comics and continuity paired with the emotional subplots of characters are given priority. I would therefore contend that one reason why superhero comics of the present era are struggling is that they are not, in my estimation, actually embodying the genuine elements of the genre, but are rather choosing to become self-referencing soap operas constantly using hyperbole to sell a story, and not using action to actually tell one.

Necrosha

As previously discussed, the main issue with X-Necrosha is not that it has a large superhero team fighting a villain in a fairly conventional plot. Superhero stories are like fairy tales, they almost always follow a typical plot. Just like every other kind of genre writing, the repetition of certain elements is exactly what makes this kind of story appealing to its audience. The problem with X-Necrosha is that it is in too much of a rush to tell the story that it is actually supposed to tell. Instead of using the artwork and paneling to pace an interesting action story, X-Necrosha glosses over the story it is supposed to tell in lieu of setting up in-continuity references and emotional moments.

Here is the first page I offer up for analysis (my apologies for the quality of the scans), from Zeb Wells, Diogenes Neves, Kevin Sharpe, and John Rauch:

In this example, the X-Man (err woman) Magik (in yellow) confronts the resurrected mutant character Tarot. Magik, possessing magical abilities and a unique soulsword, is able to overcome the abilities of Tarot, who can summon specters from Tarot cards. While the coloring and artwork is pleasing (though I think the pink hues of Tarot and her teammates do not fit well with the mood), when one looks at the panel transitions on this page, especially panels two through four, a disturbing pattern begins to emerge that has important implications for a discussion of the superhero action story format.

Here is the first panel again:

Magic approaches from the left, her soulsword drawn. It is important to note that while Tarot's powers have been demonstrated in other places in the series, in no panel do we see Tarot doing any action to actually summon the specter of Death to battle. The only cue we are given that this particular action has already occurred is the presence of tarot in the background and the fact that she is holding a tarot card. Yes, that little grey blob in her hand is the signifier that Tarot has completed all of the actions necessary to summon Death to the battlefield. This is the first example of the extreme form of action compression that modern comics now embodies.

However, an even more egregious example of action compression is demonstrated in the very next panel:

Here, Tarot reacts to the fact that her specter of Death has been dispelled by Magik. Tarot specifically says "How are you doing that?!" However, in a cruel twist, the reader is given absolutely no indication of what Magik has done. It is only the final panel of this page, panel four, where we see Magik swing her sword, that that the reader is given any clue as to what has happened between panels two and three.

And this is the disappointing reality of modern superhero paneling and its subsequent pacing. The second panel of this page is a promise. Magik draws her sword to confront the specter of Death. The imagination of the reader has been stoked. An epic confrontation is at hand. A real fight of consequence is about to occur. But just as the reader's expectations are stoked to a crescendo, nothing happens. An entire battle, an entire confrontation happens between the panels. The reader does not even see Magik strike the specter with her sword. Even the act of effortlessly banishing Death is left to the imagination of the reader. The strategy of the creative team of this comic is to employ subject-to-subject transitions to tell the story. And it is this strategy that fails utterly to tell engaging action stories.

Next time, I will give more examples of action compression, as well as examine the decompression used in this story.

Wow that is one extreme example. I hadn't a clue what was going on until you explained it.

ReplyDeleteI've always had a problem with stuff like this where characters just jump from situation from situation without any explanation of how they got there.

Though I should point out that it can be taken too far in the other direction. I hope you'll go into this as well. While there's little I find more annoying that a character giving a doctoral rhesus while in the middle of a flying kick, I've also read comics where a single issue covers a dinner conversation between two people and then it's "To be continued."